June 14 marks Flag Day, which this year marks the 240th anniversary of the date when Congress officially designated the Stars and Stripes as the official flag of the United States of America. For this month’s Revolutionary NJ blog post, we asked former Crossroads President Kevin Tremble to share his journey in discovering the designer of the flag.

Our flag means a great deal to me. Growing up it was always flown for our national holidays. As a veteran, I served beneath it. As a kid Mom and Dad took me to many historic places including one visit to the Betsy Ross House in Philadelphia and the story of our flag. Ha! Neither my parents nor I ever questioned the story. When I was Crossroads President I was part of the planning team reviewing National Historic Landmarks (NHL) as part of the Management Plan effort, and there was a listing for the NHL Francis Hopkinson House in Bordentown. Knowing NHL sites are very significant and remembering that Hopkinson was a signer, I made an effort to make a visit. There I met a very knowledgeable and affable fellow, Michael Skelly. Mike was anxious to help Crossroads fully appreciate Hopkinson’s significance. Thus my star studded journey began.

I was quickly made aware that my Betsy Ross “facts” were, well perhaps not totally “real”… the stuff of legends. As I dug into Hopkinson’s story, there emerged the signer, a congressman, a ratifier, an author, a poet, a song writer, a businessman, a lawyer, a federal judge and the artistic graphic designer. You can read more about this accomplished man in the Revolutionary Neighbors pages of the Crossroads website.

Since there were no images or a surviving flag representing his design, I was interested in delving into the real story of the Stars and Stripes. I began with the Congressional Resolution, June 14, 1777 where Congress recognized the need for a naval emblem and directed it:

“…be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation.”

This resolution appears among those submitted from the Marine Committee of the Navy Board. Here is where we find Francis Hopkinson, chair of the committee. He knew well the need for a distinguishing emblem for recognition at sea. Later, in 1780 he submitted payment requests to Congress for “a quarter cask of the public wine” for his flag design, the design of the Great Seal of the United States and several other government symbols. Hopkinson’s opponents worked to deny his payment without denying his claim. After an investigation Congress found that he was on the public payroll at the time and that he was not solely responsible for the designs.

While the designer was confirmed, I still had no image to visualize. What did the stars look like? I had seen five, six and eight pointed stars referenced. Mike Skelly pointed me to a story of Hopkinson’s family crest found in a bookplate. Here was a clue. It contained 3 six-pointed stars and red and white stripes! I began a search for other “6-pointers” in contemporary images. I found them on battle flags at Princeton, a headquarters flag at Valley Forge, on Liberty coins, on a Massachusetts militia knapsack, and on portraits of Generals Anthony Wayne and Baron Von Steuben. Then there is the portrait of General Washington by James Peale, 1790.

It seemed that the 6-pointed star was in common highly placed use and a part of Hopkinson’s artistic design vocabulary.

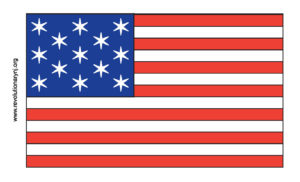

How might the “new constellation” appear? Would it be in some random arrangement, a circle, in rows or any number of ways not imagined by Congress? I found some likely connections in the unofficial predecessors to a possible Hopkinson design; the Continental Colors (the Grand Union flag) and the Commander in Chief’s standard. The frequently used Continental Colors was flown at the battle of Bunker Hill. It contains a British Union Jack in the upper left containing the superimposed crosses of St. George and St Andrew. After 1776 it was considered too confusing in battle. There is also the Commander in Chief’s flag to consider. It has 6-pointed white stars on a blue field arranged in a 3-2-3-2-3 row pattern. It seems plausible that Hopkinson would have chosen a subtle way to create new and independent imagery by linking the General Washington’s standard and our English heritage. If one looks carefully at the flag image below you can see the 3-2-3-2-3 rows form the diagonal pattern of the Union Jack crosses. Is this an accidental or deliberate design technique?

Was this Hopkinson’s Stars and Stripes?

No actual flags have survived, so the design remains somewhat mysterious. I thought this was the best we could do, and I personally commissioned a flag maker (in Philadelphia, of course) to produce one as my gift to Crossroads. I wanted to keep this marvelous story of Francis Hopkinson before us as a symbol of one of the many ways New Jersey’s people helped secure our national heritage.

One final note: I received a gift in 2016 of a limited edition reproduction of a map in the collection of the Society of the Cincinnati. It was drawn by an American engineer within days of the victory at Yorktown. As I examined the finely detailed engraving, I noted a series of cannon, drums and flags surrounding the descriptive caption of the map. There it was! A flag of 13 stripes and 13 six-pointed stars arranged as I always believed Hopkinson would have designed!

Let us take time on this June 14th to remember our Stars and Stripes man, Francis Hopkinson, patriot of Bordentown, New Jersey, our Revolutionary Neighbor.